A new reality TV show is gripping Britain. Entitled Sink or Swim, the programme gives 10 celebrities with limited to no swimming skills 12 weeks to train for a relay swim across the English Channel. One in five British adults can’t swim.

I have been training to swim the English Channel for the last 12 months (a bit more than 12 weeks!) together with my husband, Mark, and four close friends. Mark, who had a well-deserved reputation for recklessness just like Captain Matthew Webb, died unexpectedly 6 months into our training. The rest of us, are still hoping to cross as the ultimate legacy to his dream.

Eight people are reported to have died attempting to swim the channel since 1926. Not content with having outlawed swimmers setting off from its shores in 1996, the French coast guard called for a ban on cross Channel swimming altogether almost a decade ago.

The 2019 Channel ‘season’ ends in early October. With the UK due to leave the European Union at the end of the same month, what are the prospects for hundreds of swimmers already in training? Will Brexit mean that Mark’s last rites are contemporaneous with those of the epic open water swim itself?

Just in case, here’s an A to Z tribute to the iconic challenge.

A is for After Drop. Not a phenomenon peculiar to the Channel but to cold water swimming in general. More scientifically known as peripheral vasoconstriction, in cold water, the body restricts blood flow to the skin, arms and legs to protect vital organs. When you get out of the water, the cold blood from your extremities returns to your core causing a decline in body temperature. Or after-drop as it is more commonly known.

B is for Boat. Unlike merchant seaman William Hoskins who took a bale of straw with him as a support device, modern day swimmers from Captain Webb onwards, more sensibly engage a boat to accompany them. Nowadays, you can’t just choose any boat. The boats and pilots have to be licensed by the recognised channel swimming organisations. The CSA has 7; Rowena, Connemara, Viking Princess, Masterpiece, Pathfinder, Sea Leopard and Louise Jane. And the CS&PF has 6; Gallivant, Optimist, Sea Satin, Anastasia, Suva and High Hopes. Predominantly commercial fishing vessels or dive boats for the 9 months of the year when swimmers are not trying to cross the channel, you can forget the concept of a luxury gin cruiser.

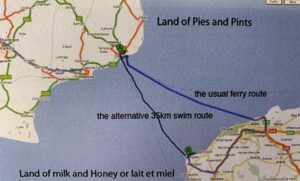

C is for Channel obviously. The stretch of water separating the North Sea from the Atlantic Ocean. It’s 34km wide and 45m deep at its narrowest and shallowest point between Dover and Cap Gris Nez. It has an average temperature in the swimming season of 15°C – 18°C. Known as the Everest of swimming, around 2,000 people have swum the Channel; around 5,000 have climbed Everest. The success rate is variously quoted from 20 to 70%. Whatever the stats, on any given day, a significant number of swimmers clearly find themselves in dire straits in Dover Strait.

C is for Channel obviously. The stretch of water separating the North Sea from the Atlantic Ocean. It’s 34km wide and 45m deep at its narrowest and shallowest point between Dover and Cap Gris Nez. It has an average temperature in the swimming season of 15°C – 18°C. Known as the Everest of swimming, around 2,000 people have swum the Channel; around 5,000 have climbed Everest. The success rate is variously quoted from 20 to 70%. Whatever the stats, on any given day, a significant number of swimmers clearly find themselves in dire straits in Dover Strait.

D is for Diet. In the heroic old days, swimmers are reported to have consumed all manner of gastronomic delights from roast beef sandwiches to rice pudding and whole roast chickens washed down with beer, brandy or Bovril while treading water. How they managed that with swollen tongues from the saltwater is anyone’s guess. In today’s more scientifically advanced world of sports nutrition, swimmers are commonly given maltodextrin carbohydrate flavoured with cordial and a little bit of food. Popular food options for swimmers include swiss rolls, bits of banana, jelly babies, canned peaches and Mars bars. Swimming the channel to lose weight is a misnomer. Swimmers commonly put on weight deliberately to help insulate them from the cold.

E is for England and the spirit of Dunkirk and D-day. Oh, sorry that’s back to D. Perhaps it should be for British eccentricity – see below. England’s open water swimming army is headed up by Freda Streeter MBE known as the Channel General. Freda directed training on the beach from a deckchair in Dover for 33 years. She’s coached or cajoled 100s of aspiring Channel Swimmers including reporter Cliff Golding. Before asking her to coach, Cliff wanted to know if Freda had ever swum the channel and she replied “Do I look that stupid?”.

F is for France. One article that I read said ‘Francophobes will be pleased to learn that only six French citizens have swum the Channel, perhaps because in France, British eccentricities are disdained.’ That has to be utter nonsense as even I can name several accomplished French citizens who have crossed to the ‘other side’. From the Gallic flair displayed by Sylvain Estadieu, aka the Flying Frenchman who swam butterfly in 2012 to the inspirational courage of Philippe Croizon, the first quadruple amputee to swim who said he would like to complete the dare ‘for myself, my family and all my fellows in misfortune who have lost their taste for life’.

Patrice with the Tenacious Turtles who travelled to France and sought him out following their successful channel swim August 2019

The French not only demonstrate flair and courage but also camaradie. Patrice Chassery whose son Arnaud has swum the Channel, stakes out the French coastline taking photos of swimmers he has invariably never met who he sees climbing out of the water at Cap Gris Nez and posting them on facebook. And anyway, who says only the English are eccentric – what about French born footballing star Eric Cantona who pledged to swim the English Channel if 10,000 people said they liked French lager.

G is for Graveyard, a stretch of water known as the swimmers’ graveyard of dreams just off the French coastline, notorious for strong currents that will sweep even a fresh swimmer into the Calais ‘no go’ area or directly south along the French coast. Most unsuccessful swim attempts heartbreakingly fail in the last few kilometres.

H is for Hazard to your Health be it Hypothermia, Hydrophobia, a non-functioning Hypothalmus or the Heebeegeebees (anxiety about the horror of it all). It’s even the subject of an article – the Perils of Swimming the English Channel in the British Medical Journal.

All swimmers have to pass a medical and undergo a qualifying swim in cold water (soloists 6 hours, relay swimmers 2 hours) and may be drug tested!! While you can channel your inner Wim Hof, and eat a lot of pizza to fatten yourself up, hypothermia is notoriously difficult to predict or spot especially when one of the signs of it is irrational behaviour. Er, like attempting to swim the channel in the first place?

I is for Immigration. Yes, you need to carry your passport. Where, is anyone’s guess. An estimated 900 migrants have crossed the Channel to date in 2019 using inflatable boats, dinghies or, unusually, swimming with the aid of a myriad of buoyancy devices. In July, the French coastguard rescued a hypothermic migrant swimmer with flippers and a rubber ring. A few days ago, an Iraqi man wearing plastic bottles to keep him afloat was not so lucky.

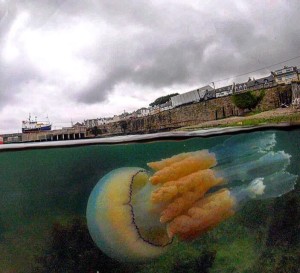

J is for Jellyfish. Swimmers will encounter sewage, oil slicks, plastic waste and patches of tangled seaweed but it was jellyfish that terrified Lewis Pugh on his heroic swim of the length of the Channel in 2018. He endured multiple stings including in the groin. Swimmers report great swarms of them and invariably post a look out in an (often vain) attempt to direct swimmers around the blooms. Even Captain Webb is understood to have covered his bathing suit in wire mesh in an attempt to stave off the jellies.

J is for Jellyfish. Swimmers will encounter sewage, oil slicks, plastic waste and patches of tangled seaweed but it was jellyfish that terrified Lewis Pugh on his heroic swim of the length of the Channel in 2018. He endured multiple stings including in the groin. Swimmers report great swarms of them and invariably post a look out in an (often vain) attempt to direct swimmers around the blooms. Even Captain Webb is understood to have covered his bathing suit in wire mesh in an attempt to stave off the jellies.

K is for King (and Queen) of the Channel. Bestowed by the Channel Swimming Association on the person that has completed the most crossings. The current titular holders are Kevin Murphy (34 swims 1968 – 2006) and Alison Streeter (Freda’s daughter) (43 crossings 1992 – to date). With the exception of a Bengali swimmer who was King for 14 years, only British and Australian men have been Kings to date. Queens on the other hand have been more diverse in their origins spanning America, Canada, Denmark and Britain.

L might be for life changing. Certainly, it’s a very specific dream. Soloists invest years in planning and training; a singular aquatic calling that eats up hours of passion, time and groceries. According to the current King, afterwards, a swimmer feels like he or she can walk on water, let alone swim in it; nothing it would seem is impossible after setting foot on the other side. Many become obsessed by the desire to conquer other watery expanses – the Triple Crown or the Oceans Seven. For some, like me, it is the journey itself. There is some sort of solace from achingly cold water in the quiet company of other people who share my sense of loss. It’s as if the cloak of the water somehow subsumes and numbs the heartache and ever-present anger as to why. Out there, the sun rises and falls along with the tides in a primeval and essential way unlike the hubbub of daily life that rudely, barely drew breath to pause, even though my life just stopped in its tracks 6 months ago. Much has been written about cold water and depression and open water swimming and stress and anxiety. It’s hard for me to explain save to say Charlie Connelly’s beautiful words on its strange appeal resonate so deeply with me (although I am filled with horror at the prospect of coming face to face with a seal).

M could be for La Manche (or the Sleeve as the French call the Channel) but a more common M would be for mal de mer; sea sickness. Responsible for the failure of many an attempt, the Channel is renowned for it. An affliction accentuated by the parachutes, sea anchors and drogues that many of the pilots trawl to slow their boats to match the pace of flailing and exhausted swimmers. Anecdotally, speculative pilots have idled away many an hour and won considerable sums betting, on any given crossing, which relay swimmers will be the first to succumb.

N is for Neap. No, not a turnip in colloquial terms – that’s a neep. The Channel generally acts as an enormous funnel for the water moving into and out of the North Sea/Atlantic. At Dover, high water can be 6.8m and low can be 0.8m – a whopping 6m difference. A neap tide is a moderate tide – high tide is lower and low tide is higher. Occurring just after the first and third quarters of the moon, swimmers predominantly prefer to swim on (and generally have better prospects of success on) a neap tide as opposed to a spring tide (which has the highest flow/height range).

O is for Observer. An official one. Such was the incredulity (and competition to be the first to cross) a healthy cynicism developed in the late 1870s about claims to have crossed the Channel. Nowadays, the two ratifying organisations (the Channel Swimming Association or CSA and Channel Swimming and Piloting Federation or CSP&F) require soloists and teams to subject themselves to an observer. Better that than to have people claiming that, if they didn’t see it, it didn’t happen. Not such an issue today in the world of satellites, drones and spyware but nonetheless every swim is observed before being verified.

P is for Pebbles. Forget rocks in your head, Channel swimmers aspire to put pebbles in their pants. Such is the drive for land and the other side that Channel swimmers have an inexplicable imperative to souvenir geological samples from French beaches. And to get them back to the pilot boat, there’s only one place they can go. Makes it all worthwhile you see.

Q is for Quadruple. Four people have achieved a triple crossing but no one has completed a quadruple. Our coach, Chloe McCardel, attempted it in August 2017. Sarah Thomas from Colorado is attempting it in September 2019. In 2017, Sarah swam into the record books by swimming ‘a century’ – a non-stop solo swim of more than 100 miles. She has a Kickstarter campaign to make a documentary about her English Channel quad attempt called ‘The Other Side’.

R is for Rules. One (certainly not two) latex or silicone hat, goggles and a compliant swimsuit – see below. Just like in Finding Dory, whatever you do, don’t touch the boat! Swimmers must stand on the shore before starting and when finishing, unassisted, on the other side. And relay swimmers must swim one hour each in the same rotation as they began. One swimmer fails, the whole team fails. The ultimate corporate team building escapade.

S is for Shipping. The Channel is widely acknowledged as the busiest shipping area in the world with over 500 ships a day. Following numerous accidents, the Dover Traffic Separation Scheme was established in 1967. The world’s first radar-controlled scheme mandates that vessels travelling north must use the French side, travelling south the English side. A 50,000 tonne container ship travelling at 25 knots requires more than a mile to stop. Kaimes Beasley of the UK’s Maritime and Coastguard Agency said in 2010 that cross-Channel swimming was “as dangerous as trying to cross the M25”. The Dover Coast Guard gives position reports of swims-in-progress in their hourly shipping broadcast and requests “a wide berth”.

S is for Shipping. The Channel is widely acknowledged as the busiest shipping area in the world with over 500 ships a day. Following numerous accidents, the Dover Traffic Separation Scheme was established in 1967. The world’s first radar-controlled scheme mandates that vessels travelling north must use the French side, travelling south the English side. A 50,000 tonne container ship travelling at 25 knots requires more than a mile to stop. Kaimes Beasley of the UK’s Maritime and Coastguard Agency said in 2010 that cross-Channel swimming was “as dangerous as trying to cross the M25”. The Dover Coast Guard gives position reports of swims-in-progress in their hourly shipping broadcast and requests “a wide berth”.

T is for togs, budgie smugglers, dick stickers, swimmers. Call them what you will. Captain Webb wore a red silk suit. The first woman to cross the Channel, Gertrude Ederle, a form fitting knitted wool tank suit. These days, notwithstanding the technological advances of FINA approved performance suits or neoprene dependent triathletes, the rules are simple – one standard issue swimming costume – sleeveless and legless.

T is for togs, budgie smugglers, dick stickers, swimmers. Call them what you will. Captain Webb wore a red silk suit. The first woman to cross the Channel, Gertrude Ederle, a form fitting knitted wool tank suit. These days, notwithstanding the technological advances of FINA approved performance suits or neoprene dependent triathletes, the rules are simple – one standard issue swimming costume – sleeveless and legless.

U is for Unpredictable. The Channel swim season runs from late July through early October. Each boat (see B for boat) divides the season into ‘windows’ or tides and allocates (usually) 5 positions on the tide. A swimmer reserves a slot with a licensed boat captain, often more than a year in advance. The weather is notoriously unpredictable and all that forward planning may be for nought if the sea is wild or the fog rolls in. The boats may simply not go out. Sometimes a full week may even pass when they will sit in port and the swimmers from all 5 slots will return home, broken-hearted, never having had the chance to swim out from the infamous white cliffs and pit themselves against the currents.

V is for Vaseline. Or more commonly, a mix of lanolin and petrolatum bought for £7 a jar at the Boots drugstore in Biggin Street. Captain Webb simply smeared himself in porpoise oil. Unsatisfied with natural prophylactics or high street pharmacy supplies, Eric Cantona claimed that he would be assisted by celebrity chef Michel Roux Jr, who boasted that he would produce a top class Michelin swimmer’s grease to lubricate Cantona. Michel said “Not only is my graisse de canard magnificent with potatoes, it will also guarantee any Channel swimmer glides through the water with elegant ease.” Michelin starred on not, CSP&F swimmers are required to avoid fouling the boat and equipment with grease following a swim by donning clothes immediately.

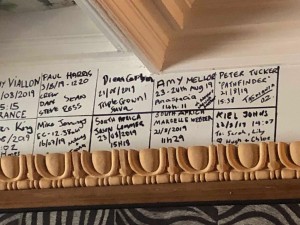

W is for the Writing on the Wall. More last writes than last rites, time has been called at the White Horse, the Dover pub where successful swimmers used to write their names on the wall. The pub has run out of space and having also consumed the ceiling, the words have moved on to Les Fleurs.

W is for the Writing on the Wall. More last writes than last rites, time has been called at the White Horse, the Dover pub where successful swimmers used to write their names on the wall. The pub has run out of space and having also consumed the ceiling, the words have moved on to Les Fleurs.

X is for crossing. Obviously. Or Xpensive (ok that’s a cheat). Argent, money, moula – as this American author found, swimming the channel is draining in a lot of ways.

Y – refer Freda Streeter. But in terms of why – actually, it seems many swimmers find meaning and motivation in philanthropy. From Comic Relief (David Walliams) to Stand Up 4 Cancer (Channel 4’s Sink or Swim), millions have been raised by both successful and unsuccessful swimmers to lend meaning to their quests. One charity, Aspire, even specifically trains people to swim across. In the spirit of gladiators, gauntlets have been thrown down and great gestures of honour made. Neil Streeter (Freda’s son – it’s a family affair this Channel thing), pilot of Suva, promised one of his swimming teams that if they raised £30,000 for two cancer charities, he would paint Suva Lady Penelope Pink. He doesn’t even like pink apparently (though we assume he likes Thunderbirds). Might even help the container ships avoid her and her swimming charges. Here she is looking pretty in pink.

Z – is for Zig Zag. Owing to tidal flows, swimming anything resembling a straight line is rare. Even Trent Grimsey who holds the current record for the fastest swim in just under 7 hours had to contend with one tide change. Jackie Cobell who holds the record for the slowest successful swim of almost 29 hours would have swum through four tide changes and is reported to have swam 105 km. Captain Webb owes much of his success to his boat men and pilots. Notwithstanding modern-day computers that can calculate courses that factor conditions and an individual’s swimming ability, swimmers are still reliant on the skills of their pilot. Ours is called Reg. We’ll be offering to buy him a pint or two if he gets us across. Oh and Reg, if we raise over A$25,000, will you paint the Viking Princess orange in honour of Can Too (it’s actually a viking colour and will co-ordinate much better with our togs)?

You can live track our swim zig zag here some time after 19 September.

Sink or swim? Only time will tell.